Professor Akbar S. Ahmed

The 21st century appears to present a very gloomy picture, at least to the great thinkers of our time. From Bernard-Henri Levy to Yuval Noah Harari to John Mearsheimer to Henry Kissinger, they point to the devastation brought by climate change, the potential dangers of Artificial Intelligence and the widespread political violence emerging out of ethnic and religious conflicts. Looming over the misery of ordinary lives is what Mearsheimer calls “great power rivalry,” when the individual is further forgotten and dominated by the vast resources and political power of the hegemonic nations.

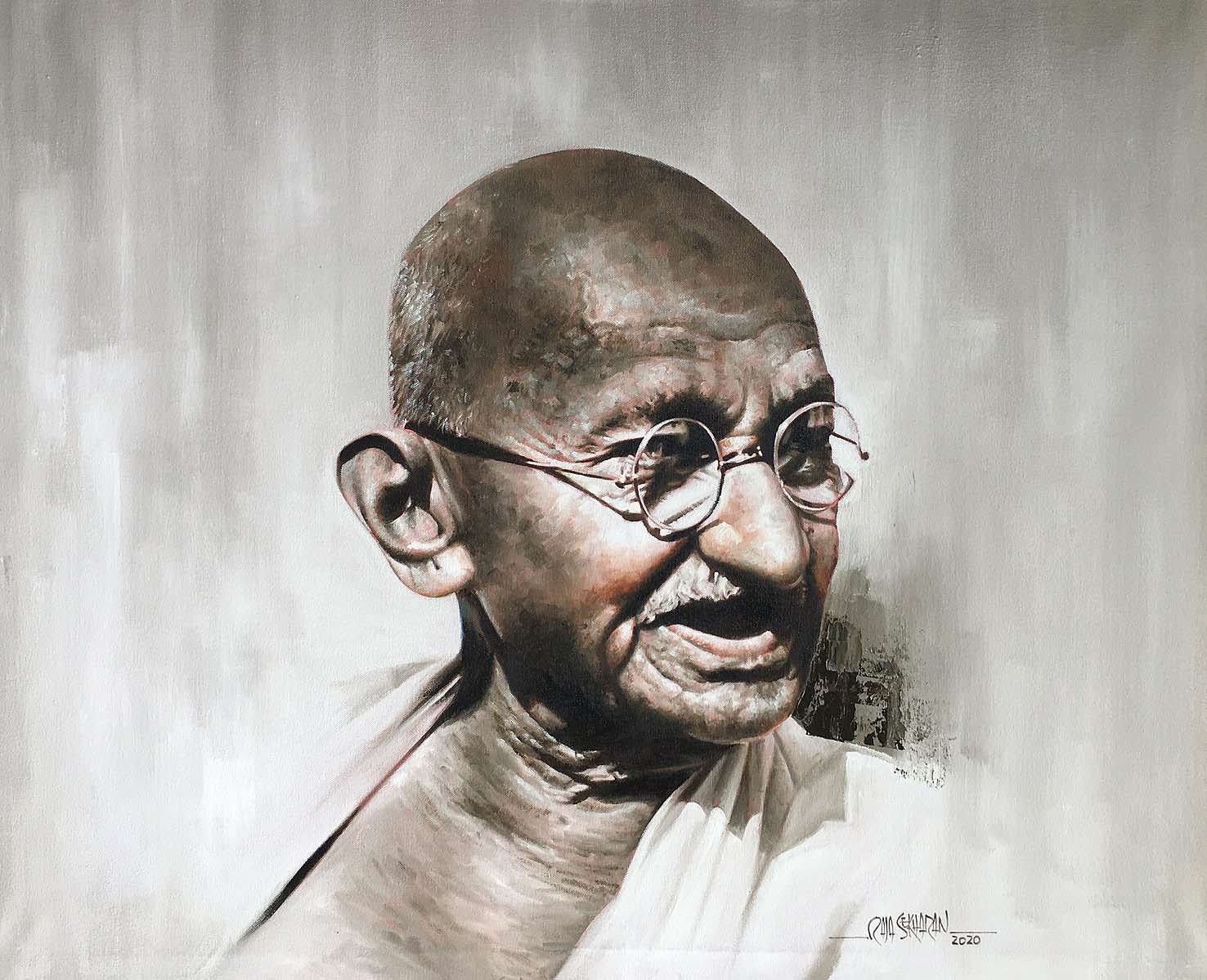

It is here where the humility and compassion of the Mahatma are more relevant than ever. With so much widespread violence between communities, leaders would be wise to heed the Mahatma‘s pungent saying, if all believe in an eye for an eye, soon the whole world will be blind. On top of all this—or because of it—commentators suggest we may be sleepwalking into a third world war, one that may well end human life as we know it on the planet.

In order to alleviate this widespread gloom and misery the world desperately needs universal philosophies to embrace the different sections and shapes of human societies. It is in this context that the ideas and example of Mahatma Gandhi become most relevant. His idea of ahimsa nonviolence, shanti peace and seva service to people – and of course satyagraha or non-violent struggle for justice–are the most powerful and relevant aspects of his philosophy for today’s world.

His idea of ahimsa nonviolence, shanti peace and seva service to people – and of course satyagraha or non-violent struggle for justice–are the most powerful and relevant aspects of his philosophy for today’s world.

For me these values are embodied in his reaching out to those not of his faith for example the Muslims. This is what makes him a true saint. He went out of his way to show respect and acceptance for the minority. For example he wrote the Foreword to the life of the prophet of Islam, read from the holy Quran in his morning prayer and chanted his favorite hymn which included both ishwar and Allah.

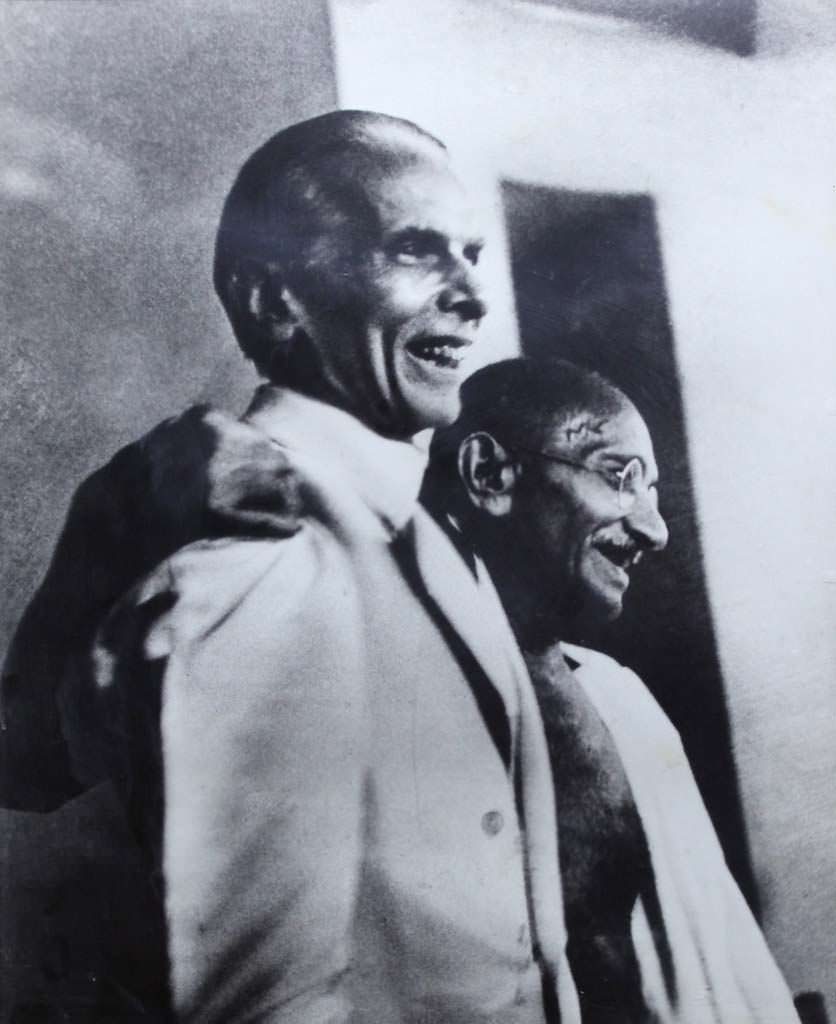

The Mahatma showed once again his inclusive embrace of humanity when even after the bloody and bitter Partition in 1947 he declared that he would spend three months of every year in Pakistan as for him the peoples of both nations were close to his heart. Mr. Jinnah’s response was equally magnificent. He ordered his staff that full protocol be provided for the Mahatma as given to a head of state.

Perhaps that is why he was assassinated. But that is precisely what in my eyes and the eyes of millions makes him a superhero for the ages.

The Mahatma presents us with the great Indian paradox. If a true aristocrat is to be defined by courtesy and good manners, then the Mahatma was no less than the most refined princes and maharajas of India. His respect and courtesy were legendary in showing grace and courtesy even in times of acrimony and division. He wrote, as we said previously, the foreword to a book on the Prophet of Islam and he addressed Mr. Jinnah, a political opponent, with the title given to him by his supporters, the Quaid-I-Azam.

My third point is to ask ourselves what are the principles of Gandhian behavior we need to remind ourselves of? What are we to extract from a life so rich? Despite the shameful attacks on his reputation online, what we need to share and propagate are the great Gandhian virtues of ahimsa, shanti and seva. Not only India but the world needs these Gandhian values. When he heard the Mahatma was killed, Mr Jinnah, the Quaid I Azam, issued an immediate message of condolence. He used the word great four times to describe the Mahatma adding the Muslims of India had lost their greatest supporter.

To my mind, the reconciliation of these two great men of history is the inevitable destiny of the subcontinent and will bring peace and harmony to this vast and troubled region of the planet.

Both leaders would have been heartbroken to see the condition and predicament of the minorities in their respective nations. To my mind, the reconciliation of these two great men of history is the inevitable destiny of the subcontinent and will bring peace and harmony to this vast and troubled region of the planet. That is why my latest play “Gandhi and Jinnah return home” ends with the last scene of the two giants of the Subcontinent embracing and acknowledging each other. He is correctly called the Quaid-i-Azam, says the Mahatma and Jinnah replies, he is indeed the Mahatma.

Our South Asian Subcontinent in the last century elevated the Mahatma to an icon and then forgot his true message; we have to, all of us, revive the essence of his message for the 21st century. Most important: the Mahatma urged thinking people to begin the process of change at home: become the change you wish to achieve. He does not need us; we need him.

Akbar Ahmed is Distinguished Professor and the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies, School of International Service, American University, and Wilson Center Global Fellow, Washington DC. He was the former Pakistan High Commissioner to the UK and Ireland.

- This article written exclusively for the Khalili Foundation is based on my talk delivered at the Karnataka Gandhi Smaraka Nidhi in Bangalore, India.